BETWEEN THE

SIXTH

AND 7TH FLOOR

Macie Calvert

27 December 2023

27 December 2023

There is a man on the roof, and he is throwing keys. It is so dark that he sees them only for a moment as they fly, a dappling of gold reflected from the streetlights below before they fall, the city too loud for any sound to be made when they fall. Sometimes he hurls one as if in anger. Other times he throws them like seeds, scattering them in the wind.

The man stops, head swiveling like a hunting dog catching the scent of something. As if he has (impossibly) heard someone or something in the twelve floors below him. He grabs another fistful of keys—presumably the last of it—and chucks them over the ledge of the roof, and then disappears into the hotel.

—

Twelve stories below, standing in front of the very same hotel, there is a woman in a trench coat on the sidewalk, grinding a cigarette butt into the pavement with the heel of her shoe. Under the brim of her hat, her lips are pursed tightly, shoulders rigid but determinedly pushed back. Her name is Marceline.

She received an anonymous tip an hour ago, from someone who called the agency imploring one of the investigators to pay a visit to the Reverie Hotel. Marceline is not ecstatic to go alone, especially after dark.

The Reverie Hotel is not a functioning hotel. It is long abandoned, built in a different century, the kind of place teenagers sneak into on dares. It looks out of place on this block, sad, the way things that were once grand in another time are in the present day, haunted—

Marceline yelps as if she has been punched at the sudden, light tap on her shoulder, as if from someone standing behind her. Something clinks to the ground. It is a key, fallen from the sky. Marceline’s heartbeat is audible. As if to tell herself there is nothing to worry about, she laughs. Probably fallen off a rooftop by accident—

A few feet in front of her, keys shower onto the ground, clattering onto the pavement and into the gutter, at least three dozen.

Marceline gawks for a moment, feeling as if she is on some strange movie set, and then picks one up, examining it as she approaches the doors of the hotel. There is no engravement, no apartment number. Just a little gold key, the same as the handles to the doors of the Reverie. Marceline knocks, and then, after a moment’s debate, inserts it into the lock. There is no squeak, nothing to indicate age or wear as the door opens.

—

Someone is in the hotel. The man with the keys is sure of it. He listens from the twelfth floor; he hears footsteps in the lobby. And then (he marvels at this) he hears the unmistakable ding of the elevator below. There is one elevator in the Reverie. The indicator at the top of the doors of the ornate cage elevator moves slowly from one to two, where it stops.

He knows that isn’t accurate though. The elevator is unpredictable and strange, like the rest of the Reverie. Sometimes he comes out on floors he didn’t know existed. But he knows how to find anyone who enters the hotel, because they all end up on the same floor first.

When the elevator (which is painted in gold and carpeted in velvet, and resembles a birdcage) reaches the twelfth floor it is empty, and he steps inside.

—

Marceline knows what she is doing is ridiculous. She reflects on this as the elevator rises. She feels as if something interesting is about to happen, something unexplainable, like the keys. There is music faintly playing, as if from one of the floors, but she cannot make out a direction, so it appears to simply float all around her. Barely-there but in her ear, a woman faintly singing. The lift moves through darkness again, soundlessly, until dim blue light slits through the spindly golden bars.

Marceline at first thinks there is a pool in the room, and then she thinks that she has stepped outside somehow, but then remembers that it is past midnight outside, and the sky—the ceiling, no, the light, everything in this room is bathed in a too-vivid, deep lapis blue, pressing into her eyes like a physical force. As if a child had been asked to draw a picture of the ocean, everything unrealistically bathed in color.

As she steps into the room, water laps against the toes of her shoes. Tiny waves. Water stretches as far as she can see, creeping toward the elevator doors. An ocean more than a pool.

“Flooded,” she says under her breath, but the word is a question, not a diagnosis. She kneels down and dips her fingertips into it, then lifts it to her lips. Saltwater. As she straightens up she realizes that there is something gritty against her knee. Sand.

“Did you pick up one of the keys?”

Marceline turns around. She is too curious, too amazed, to be scared. There is a man dressed in black standing behind her, in the space where the water melts into the sand.

“How is this—I mean, is it flooded?” she says.

“How did you get inside?”

“The door was unlocked,” Marceline says. She holds up the key. “This belongs to you?”

“It’s not flooded,” he says, disregarding the latter question. “This is just the room.”

Marceline would not define this place as a room. She doesn't feel as if she is outside—there is no wind as if on a real beach, and yet there are no visible walls, no ceiling, no floor that is not sand or water. All she can see is blue light around her, obscuring any horizon line for the water.

“How is this possible?” It is an optical illusion, she thinks. She is in some sort of trick, a magic show.

“Why did you come inside?” the man (magician?) says.

“I got a call,” she blurts, forgetting to be wary. She can still hear the music, faint through the light. “I’m a private investigator.” She is sure that there is danger here, but she does not feel afraid. “Is everything all right?”

“Of course. I assume it was a noise complaint?”

“Yes.”

“I can show you, if that’ll clear things up. Don’t want any trouble.” His expression is hard to make out in the dimness. He is smiling, though, the way a salesperson smiles, his voice a sort of practiced drone. Marceline follows.

—

In the elevator, the floor indicators move upward while the lift itself moves downwards, from six to seven, sinking. It takes too long to have just been one floor. A minute passes, then two. Through the cracks, Marceline sees black brick, and then a flash of a room: a garden, all shades of emerald, thick as a jungle. Black brick, and a room that looks impossibly large to fit into one hotel, as large as an opera house. Black brick, and a dark-wood library, leather and cigarette smoke. Black brick, and a stretch of dark water, wreathed in weeping willow branches.

“Why did you take the key?” he says.

“What?”

“The key on the ground. You picked it up.” His eyes narrow, but he is smiling. There is something about him that reminds her of an actor, everything about him too theatrical and vivid, from his all-black clothes to his pale skin, as if he is in a costume, playing a role.

Now it is her turn to ignore his question. “How did you build this?”

“I didn’t build it.”

In the next room, the leaves of trees overhead block out the walls and ceiling. Warm, soft light that had to be daylight, not electric, filtered through the leaves. So many trees, trees with long, thin tresses, trees with trunks like bent limbs, thicker than a human head, branches bent so parallel to the ground she could walk up in her heels.

“This is the only room I can think of that could cause noise. The animals, sometimes.” Animals? Marceline does not think he is talking about cats and dogs.

Something in the back of her head tells her that this room, this garden, though otherworldly, is benign. That no harm will come to her while she is here, in this mass of gentle greens punctuated by starbursts of color, fuschia and pale yellow and lavender. Like a painting.

“Is anyone else here with you?” Marceline says. “Do you run the hotel by yourself?”

“No. Just you.”

When the doors open once more, they are back in the lobby. The man is watching her, a pleasant, slightly embarrassed expression on his face, like, nothing to see here. It crosses Marceline’s mind that perhaps he was the one who made that call, to lure her to this vibrant pocket in the city that blurred the line in her head between performance and truth.

As Marceline steps through the doors, she glances back. He is not there; the elevator doors are already shut. Outside, she blinks from the sun slitting against her eyes, the quiet of the hotel harsh against the bustle of the city awake.

—

Somewhere, away from where Marceline is now, the man peers outside the window and thinks of the little gold keys scattered across the city like loose change. Some will never be touched again, he thinks. Some will fall into gutters and some will get crushed underfoot until they are the same color as the street. But some—and he knows this to be true—will be picked up. There is a certain person who picks up something pretty or strange from the ground or a windowsill, and a certain person who begins to wonder what it unlocks.

—

Marceline stands in a telephone booth, letting the line ring. She waits for a minute, then more. No operator’s voice comes on the line. Only the drilling ringing, on and on. Slowly, Marceline lowers the phone and squints through the glass of the booth to the sunlit street. Sunlight. It is not day time right now.

If she listens very closely, Marceline can hear it: the same song that plays throughout the hotel, a woman faintly singing, from another floor far away.

The man stops, head swiveling like a hunting dog catching the scent of something. As if he has (impossibly) heard someone or something in the twelve floors below him. He grabs another fistful of keys—presumably the last of it—and chucks them over the ledge of the roof, and then disappears into the hotel.

—

Twelve stories below, standing in front of the very same hotel, there is a woman in a trench coat on the sidewalk, grinding a cigarette butt into the pavement with the heel of her shoe. Under the brim of her hat, her lips are pursed tightly, shoulders rigid but determinedly pushed back. Her name is Marceline.

She received an anonymous tip an hour ago, from someone who called the agency imploring one of the investigators to pay a visit to the Reverie Hotel. Marceline is not ecstatic to go alone, especially after dark.

The Reverie Hotel is not a functioning hotel. It is long abandoned, built in a different century, the kind of place teenagers sneak into on dares. It looks out of place on this block, sad, the way things that were once grand in another time are in the present day, haunted—

Marceline yelps as if she has been punched at the sudden, light tap on her shoulder, as if from someone standing behind her. Something clinks to the ground. It is a key, fallen from the sky. Marceline’s heartbeat is audible. As if to tell herself there is nothing to worry about, she laughs. Probably fallen off a rooftop by accident—

A few feet in front of her, keys shower onto the ground, clattering onto the pavement and into the gutter, at least three dozen.

Marceline gawks for a moment, feeling as if she is on some strange movie set, and then picks one up, examining it as she approaches the doors of the hotel. There is no engravement, no apartment number. Just a little gold key, the same as the handles to the doors of the Reverie. Marceline knocks, and then, after a moment’s debate, inserts it into the lock. There is no squeak, nothing to indicate age or wear as the door opens.

—

Someone is in the hotel. The man with the keys is sure of it. He listens from the twelfth floor; he hears footsteps in the lobby. And then (he marvels at this) he hears the unmistakable ding of the elevator below. There is one elevator in the Reverie. The indicator at the top of the doors of the ornate cage elevator moves slowly from one to two, where it stops.

He knows that isn’t accurate though. The elevator is unpredictable and strange, like the rest of the Reverie. Sometimes he comes out on floors he didn’t know existed. But he knows how to find anyone who enters the hotel, because they all end up on the same floor first.

When the elevator (which is painted in gold and carpeted in velvet, and resembles a birdcage) reaches the twelfth floor it is empty, and he steps inside.

—

Marceline knows what she is doing is ridiculous. She reflects on this as the elevator rises. She feels as if something interesting is about to happen, something unexplainable, like the keys. There is music faintly playing, as if from one of the floors, but she cannot make out a direction, so it appears to simply float all around her. Barely-there but in her ear, a woman faintly singing. The lift moves through darkness again, soundlessly, until dim blue light slits through the spindly golden bars.

Marceline at first thinks there is a pool in the room, and then she thinks that she has stepped outside somehow, but then remembers that it is past midnight outside, and the sky—the ceiling, no, the light, everything in this room is bathed in a too-vivid, deep lapis blue, pressing into her eyes like a physical force. As if a child had been asked to draw a picture of the ocean, everything unrealistically bathed in color.

As she steps into the room, water laps against the toes of her shoes. Tiny waves. Water stretches as far as she can see, creeping toward the elevator doors. An ocean more than a pool.

“Flooded,” she says under her breath, but the word is a question, not a diagnosis. She kneels down and dips her fingertips into it, then lifts it to her lips. Saltwater. As she straightens up she realizes that there is something gritty against her knee. Sand.

“Did you pick up one of the keys?”

Marceline turns around. She is too curious, too amazed, to be scared. There is a man dressed in black standing behind her, in the space where the water melts into the sand.

“How is this—I mean, is it flooded?” she says.

“How did you get inside?”

“The door was unlocked,” Marceline says. She holds up the key. “This belongs to you?”

“It’s not flooded,” he says, disregarding the latter question. “This is just the room.”

Marceline would not define this place as a room. She doesn't feel as if she is outside—there is no wind as if on a real beach, and yet there are no visible walls, no ceiling, no floor that is not sand or water. All she can see is blue light around her, obscuring any horizon line for the water.

“How is this possible?” It is an optical illusion, she thinks. She is in some sort of trick, a magic show.

“Why did you come inside?” the man (magician?) says.

“I got a call,” she blurts, forgetting to be wary. She can still hear the music, faint through the light. “I’m a private investigator.” She is sure that there is danger here, but she does not feel afraid. “Is everything all right?”

“Of course. I assume it was a noise complaint?”

“Yes.”

“I can show you, if that’ll clear things up. Don’t want any trouble.” His expression is hard to make out in the dimness. He is smiling, though, the way a salesperson smiles, his voice a sort of practiced drone. Marceline follows.

—

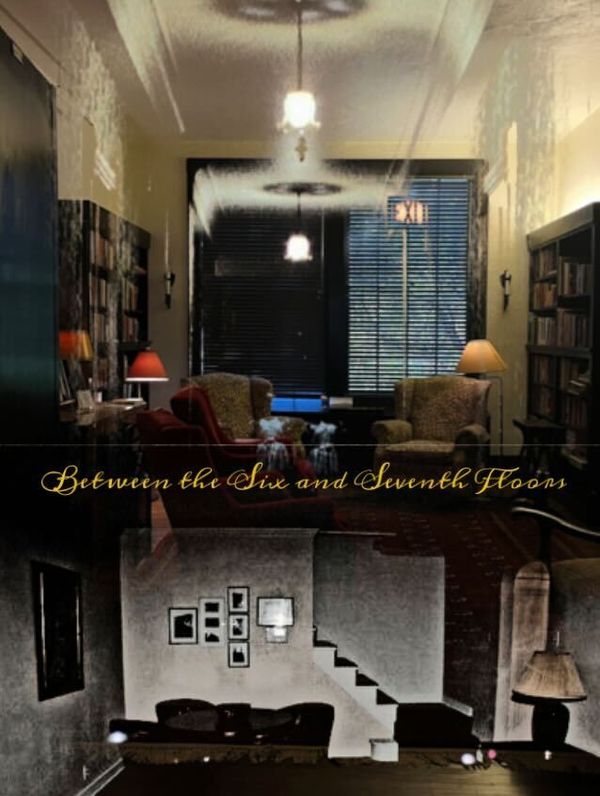

In the elevator, the floor indicators move upward while the lift itself moves downwards, from six to seven, sinking. It takes too long to have just been one floor. A minute passes, then two. Through the cracks, Marceline sees black brick, and then a flash of a room: a garden, all shades of emerald, thick as a jungle. Black brick, and a room that looks impossibly large to fit into one hotel, as large as an opera house. Black brick, and a dark-wood library, leather and cigarette smoke. Black brick, and a stretch of dark water, wreathed in weeping willow branches.

“Why did you take the key?” he says.

“What?”

“The key on the ground. You picked it up.” His eyes narrow, but he is smiling. There is something about him that reminds her of an actor, everything about him too theatrical and vivid, from his all-black clothes to his pale skin, as if he is in a costume, playing a role.

Now it is her turn to ignore his question. “How did you build this?”

“I didn’t build it.”

In the next room, the leaves of trees overhead block out the walls and ceiling. Warm, soft light that had to be daylight, not electric, filtered through the leaves. So many trees, trees with long, thin tresses, trees with trunks like bent limbs, thicker than a human head, branches bent so parallel to the ground she could walk up in her heels.

“This is the only room I can think of that could cause noise. The animals, sometimes.” Animals? Marceline does not think he is talking about cats and dogs.

Something in the back of her head tells her that this room, this garden, though otherworldly, is benign. That no harm will come to her while she is here, in this mass of gentle greens punctuated by starbursts of color, fuschia and pale yellow and lavender. Like a painting.

“Is anyone else here with you?” Marceline says. “Do you run the hotel by yourself?”

“No. Just you.”

When the doors open once more, they are back in the lobby. The man is watching her, a pleasant, slightly embarrassed expression on his face, like, nothing to see here. It crosses Marceline’s mind that perhaps he was the one who made that call, to lure her to this vibrant pocket in the city that blurred the line in her head between performance and truth.

As Marceline steps through the doors, she glances back. He is not there; the elevator doors are already shut. Outside, she blinks from the sun slitting against her eyes, the quiet of the hotel harsh against the bustle of the city awake.

—

Somewhere, away from where Marceline is now, the man peers outside the window and thinks of the little gold keys scattered across the city like loose change. Some will never be touched again, he thinks. Some will fall into gutters and some will get crushed underfoot until they are the same color as the street. But some—and he knows this to be true—will be picked up. There is a certain person who picks up something pretty or strange from the ground or a windowsill, and a certain person who begins to wonder what it unlocks.

—

Marceline stands in a telephone booth, letting the line ring. She waits for a minute, then more. No operator’s voice comes on the line. Only the drilling ringing, on and on. Slowly, Marceline lowers the phone and squints through the glass of the booth to the sunlit street. Sunlight. It is not day time right now.

If she listens very closely, Marceline can hear it: the same song that plays throughout the hotel, a woman faintly singing, from another floor far away.