THE MOON AND MAYA ARE NEIGHBORS

Khaled A.

27 October 2022

English has always felt distant — its letters disjointed, its sounds metallic, its grammar alienating. Yet it was also what many used to fully come into their bodies for the first time. There are poets who take English by the neck, witnessing the gaps it creates in our memories, and the gaps it fills in our mouths. Their imaginations bring this language closer to our tongues, even if by a couple syllables. They deconstruct English’s rules and structures and invent their own. To do so, they borrow from family albums, erased archives, lullabies, tea pots, stars, and machines. They interweave language with shapes and pictures and words we know in our stomachs. Maya Salameh is one of those poets.

Maya wrote their first poem when they were in first grade. It was about a chicken seeking companionship through a community of like-minded poultry. When I asked Maya why they felt drawn towards poetry as a medium, especially from such a young age, the answer seemed obvious: “I was a kid who had a problem with authority. Poetry was the medium with the least rules, and it’s also the most accessible.” Maya never received any formal artistic training; exploring other mediums required not only training and mentorship, but also materials and softwares their family didn’t have the socioeconomic resources to access. “I just needed a pen and paper. In that way, poetry was immediate, permeable and liberating.”

Regardless of barriers such as finances, Maya continued to explore other forms of expression. They dance and sing and perform. Maya doesn’t believe in “medium allegiances” and taps into every possible field that could inform and feed their poetry. However, “what keeps [them] coming home to poetry” is its stubbornness. Whenever they think they’ve read everything that could possibly resonate with them, they stumble across a line or verse that proves them wrong. This sense of surprise is something they most consistently find in poems.

Growing up in a multilingual household, playing across languages felt intuitive as a writing practice for Maya. While their first language was Arabic, they also speak, write, and dream in Spanish, French, and English. Each language offered and deprived Maya of certain things. Arabic is the language of love and home to them because “it’s the language mama loves [them] in.” Helping family members translate themselves in order to communicate with the world around them taught Maya from an early age the weight and privilege of English fluency. Attending a public school which offered a French immersion program added the pressure to take on a second and third language (English) from a young age. Maya was aware from this young age that English, alongside other “dominant languages,” serves as a mechanism of power and domination. Yet, in a “twisted, maybe colonial way,” they find French a very nostalgic and intimate language that was a large part of their childhood. Maya’s multilingual writing isn’t a matter of decoration– it reflects the unique and fluid world they grew up in. It is most natural for them to think bilingually, and even trilingually – to decode their experience through language.

Maya is the youngest-ever winner of the 2022 Etel Adnan Poetry Prize, a prize celebrating the work of poets of Arab heritage and named after the late Lebanese poet Etel Adnan. They are also a poet fellow of the William Male Foundation and a 2016 National Student Poet, America’s highest honor for youth poets. Maya has poems published in The Rumpus, Asian American Writer’s Workshop, The Brooklyn Review, and POETRY Magazine. But before these accolades, poetry was a secret and private ritual for them. Before performing in the White House when they were a junior in high school, Maya performed in their bedroom and family’s kitchen. After that performance, everyone referred to them as a Poet – “poet” became a new part of their public identity. Recognizing the increasing visibility of their work sparked concern about what and from where they wrote. Concerns of Orientalizing themself or confirming White Americans’ essentialist beliefs about Arab womanhood began shaping their writing process. Visibility brought a constant struggle with honesty, authenticity, and self-censorship that they still reckon with today.

![]()

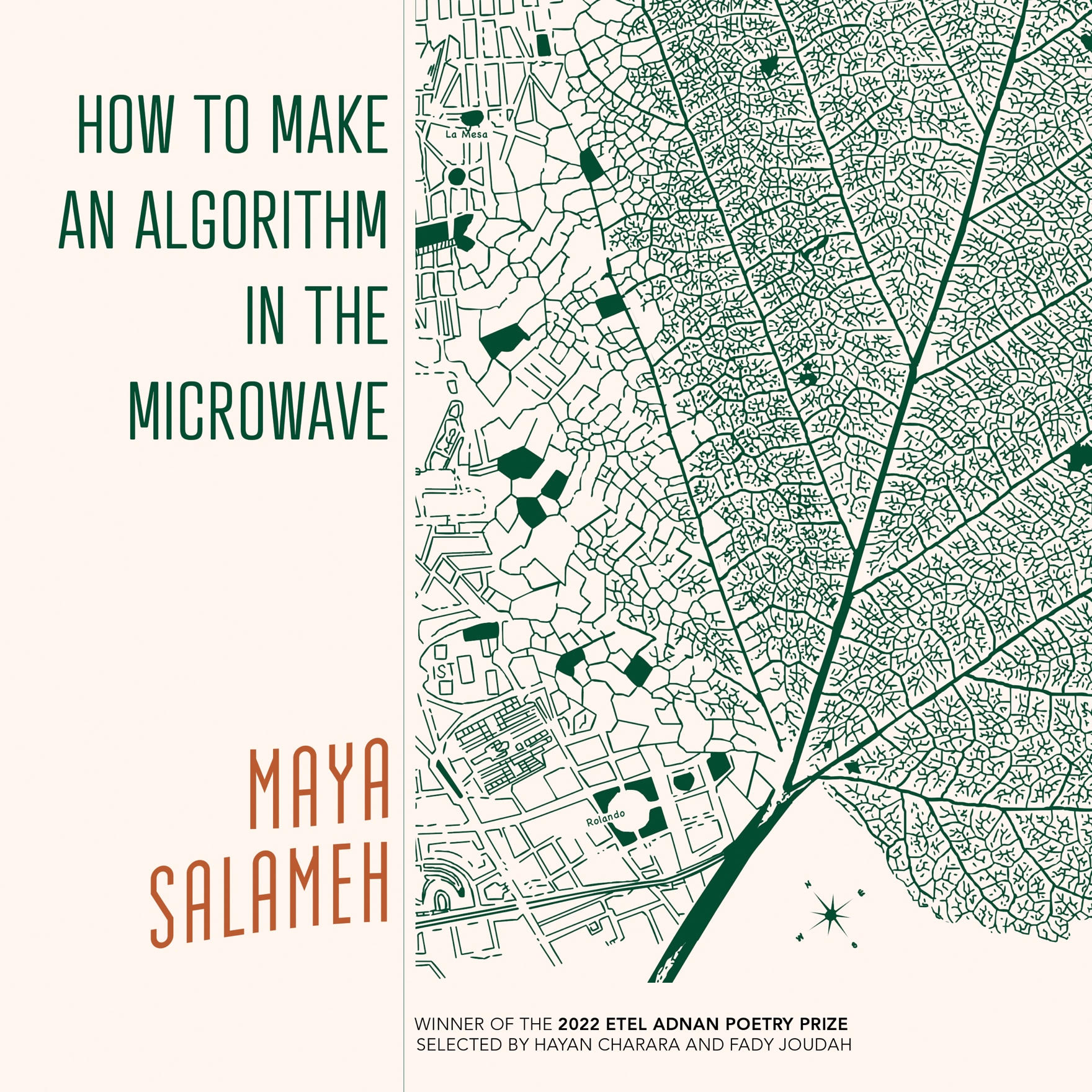

This ongoing struggle of being watched and surveilled is an essential theme of their debut poetry collection, How to Make an Algorithm in the Microwave, published this October through the University of Arkansas and their Etel Adnan Prize. These poems dissect and confront the language of the surveillance apparatus and technologies which shape the realities of the Arab American woman’s daily life. Line after line, the code Maya writes situates technology within the context of their everyday experiences: recreating personal records and archives, gender surveillance and revolution, and the ritual technologies of joy. Throughout the book, they memorialize the cities that have loved them, from Beirut to Boston to Damascus to San Diego, all through their own powerful language, talking back to ancestors and enemies alike in an accent that “might not have been invented yet.”

In the collection, Maya plays with words, pictures, and Punnett squares. They cite Joseph Masoud, Amy Winehouse, and their grandmother. In one poem, they place Fairouz and Winehouse in conversation, recalling Fairouz’s famous moniker as the moon’s neighbor (Nehna wel amer jeeran). Even before this collection, as seen in their first chapbook, rooh, their practice was always rooted in defying conventional and elitist definitions of knowledge– poetry can be found in everything and everywhere, and especially outside the rigid confines of Western teleologies of knowledge. In their spare time, they hack at a Google Doc of lines, titles, and shapes they come across in movies, music, daily conversations, or the languages their body speaks to them in. Maya pieces together their archive from the things that feed them, creating a mosaic which widens possibilities for what language can look, taste, and feel like.

Maya wrote their first poem when they were in first grade. It was about a chicken seeking companionship through a community of like-minded poultry. When I asked Maya why they felt drawn towards poetry as a medium, especially from such a young age, the answer seemed obvious: “I was a kid who had a problem with authority. Poetry was the medium with the least rules, and it’s also the most accessible.” Maya never received any formal artistic training; exploring other mediums required not only training and mentorship, but also materials and softwares their family didn’t have the socioeconomic resources to access. “I just needed a pen and paper. In that way, poetry was immediate, permeable and liberating.”

Regardless of barriers such as finances, Maya continued to explore other forms of expression. They dance and sing and perform. Maya doesn’t believe in “medium allegiances” and taps into every possible field that could inform and feed their poetry. However, “what keeps [them] coming home to poetry” is its stubbornness. Whenever they think they’ve read everything that could possibly resonate with them, they stumble across a line or verse that proves them wrong. This sense of surprise is something they most consistently find in poems.

Growing up in a multilingual household, playing across languages felt intuitive as a writing practice for Maya. While their first language was Arabic, they also speak, write, and dream in Spanish, French, and English. Each language offered and deprived Maya of certain things. Arabic is the language of love and home to them because “it’s the language mama loves [them] in.” Helping family members translate themselves in order to communicate with the world around them taught Maya from an early age the weight and privilege of English fluency. Attending a public school which offered a French immersion program added the pressure to take on a second and third language (English) from a young age. Maya was aware from this young age that English, alongside other “dominant languages,” serves as a mechanism of power and domination. Yet, in a “twisted, maybe colonial way,” they find French a very nostalgic and intimate language that was a large part of their childhood. Maya’s multilingual writing isn’t a matter of decoration– it reflects the unique and fluid world they grew up in. It is most natural for them to think bilingually, and even trilingually – to decode their experience through language.

Maya is the youngest-ever winner of the 2022 Etel Adnan Poetry Prize, a prize celebrating the work of poets of Arab heritage and named after the late Lebanese poet Etel Adnan. They are also a poet fellow of the William Male Foundation and a 2016 National Student Poet, America’s highest honor for youth poets. Maya has poems published in The Rumpus, Asian American Writer’s Workshop, The Brooklyn Review, and POETRY Magazine. But before these accolades, poetry was a secret and private ritual for them. Before performing in the White House when they were a junior in high school, Maya performed in their bedroom and family’s kitchen. After that performance, everyone referred to them as a Poet – “poet” became a new part of their public identity. Recognizing the increasing visibility of their work sparked concern about what and from where they wrote. Concerns of Orientalizing themself or confirming White Americans’ essentialist beliefs about Arab womanhood began shaping their writing process. Visibility brought a constant struggle with honesty, authenticity, and self-censorship that they still reckon with today.

This ongoing struggle of being watched and surveilled is an essential theme of their debut poetry collection, How to Make an Algorithm in the Microwave, published this October through the University of Arkansas and their Etel Adnan Prize. These poems dissect and confront the language of the surveillance apparatus and technologies which shape the realities of the Arab American woman’s daily life. Line after line, the code Maya writes situates technology within the context of their everyday experiences: recreating personal records and archives, gender surveillance and revolution, and the ritual technologies of joy. Throughout the book, they memorialize the cities that have loved them, from Beirut to Boston to Damascus to San Diego, all through their own powerful language, talking back to ancestors and enemies alike in an accent that “might not have been invented yet.”

In the collection, Maya plays with words, pictures, and Punnett squares. They cite Joseph Masoud, Amy Winehouse, and their grandmother. In one poem, they place Fairouz and Winehouse in conversation, recalling Fairouz’s famous moniker as the moon’s neighbor (Nehna wel amer jeeran). Even before this collection, as seen in their first chapbook, rooh, their practice was always rooted in defying conventional and elitist definitions of knowledge– poetry can be found in everything and everywhere, and especially outside the rigid confines of Western teleologies of knowledge. In their spare time, they hack at a Google Doc of lines, titles, and shapes they come across in movies, music, daily conversations, or the languages their body speaks to them in. Maya pieces together their archive from the things that feed them, creating a mosaic which widens possibilities for what language can look, taste, and feel like.