Radical (Rad!) Socialist/Feminist Architecture

Grace Schimmel

2022

2022

The year is 1915, and socialist-feminist-utopian-commune architecture has just become a physical reality.

BAMPFA’s current exhibit, Hippie Modernism, is subtitled: “The Struggle for Utopia.” In these particularly dystopic times, it is full of incredibly relevant ideas and visions. One particularly interesting attempted antidote to dissatisfaction with the state of society came to life with the Llano del Rio commune.

Llano del Rio exists today in the form of desolate chimney stacks and a singular silo in the sands of the Mojave off the CA-138 E in Antelope Valley, just the outline of what it once was and what it once stood for over 100 years ago.

California is littered with the remains of cult-culture, but these particular piles of stones speak in a way that’s just a bit louder than the others do. Llano del Rio came to be when political figure Job Harrison decided that the best way to convert others to socialism was to lead by example. He had previously, in 1911, come extremely close to becoming the first socialist mayor of Los Angeles. He and his legal partner, Clarence Darrow, are most well-known for defending the McNamara brothers after they were charged with the bombing of the Times building in 1910.

After losing the race for mayor, he purchased 10,000 acres of land in the Mojave Desert near the San Gabriel Mountains from the Mescal Water and Land Company and set out populating his perfectly self-sustainable socialist city.

![]()

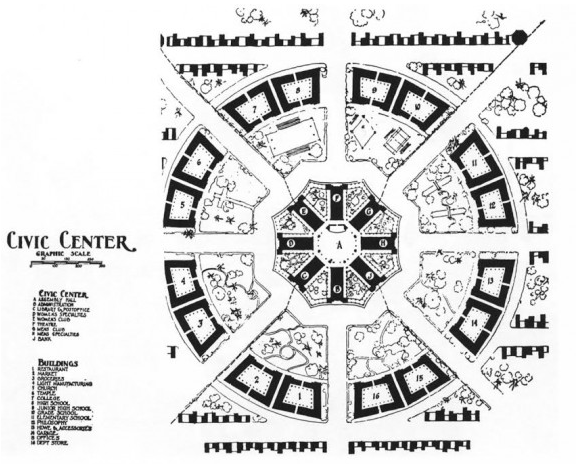

Civic Center (image from Frances Anderton’s blog)

Flyers read:

“Needs 900 single men and women and married men and their families.”

“This is the opportunity of a lifetime to solve the problem of unemployment and to provide for the future of yourself and your children.”

“We have land and water, machinery and experts for every department of production.”

“No experience as an agriculturalist needed. Men and women of nearly all useful occupations in demand. Every member a shareholder in the enterprise.”

Llano del Rio not only promised a fulfilling lifestyle, but also gender equality via architecture; Alice Constance Austin designed spaces that physically enforced and encouraged an equal playing field. Remember the year is 1915; the 19th amendment was ratified in 1920. Austin was acting on vision equally as radical as her socialist counterpart’s.

The first thing to go was the kitchen — in Austin’s mind, the agent of imprisonment. Each house was built without one; the city was organized circularly with centralized kitchens, daycares, and washing spaces. Austin even designed furniture in such a way to require less dusting via special jointing. All this was to considerably relieve the women of the colony of housework so as to have more time to actively participate in the politics of Llano del Rio.

The commune lost its water rights in 1916, and the onset of WWI lead to a mass exodus of many of its men. Llano del Rio eventually went bankrupt and finally disbanded completely in 1918.

While Llan0 del Rio sounds like an ideal existence to some, it is imperative to mention that the commune accepted only white members. This attempt at utopia was a fundamentally racist one.

The fight for kitchenless homes is reminiscent of what we call today white feminism. That is to say, the fight for liberation of middle class white women only while still using the blanket terms “women” and “feminism.” Austin’s vision did not consider women of other classes or women of other colors. So while her work was still undoubtedly done in the hopes of furthering the improvement of the status and lifestyle of women, it sacrificed and excluded the majority of them in order to realize physical actualization.

Despite its discriminatory policies, Llano del Rio remains interesting as a radical concept and as a story. Communes like this one are key components of California’s history; hit up “Hippie Modernism; The Struggle for Utopia” to learn more.

BAMPFA’s current exhibit, Hippie Modernism, is subtitled: “The Struggle for Utopia.” In these particularly dystopic times, it is full of incredibly relevant ideas and visions. One particularly interesting attempted antidote to dissatisfaction with the state of society came to life with the Llano del Rio commune.

Llano del Rio exists today in the form of desolate chimney stacks and a singular silo in the sands of the Mojave off the CA-138 E in Antelope Valley, just the outline of what it once was and what it once stood for over 100 years ago.

California is littered with the remains of cult-culture, but these particular piles of stones speak in a way that’s just a bit louder than the others do. Llano del Rio came to be when political figure Job Harrison decided that the best way to convert others to socialism was to lead by example. He had previously, in 1911, come extremely close to becoming the first socialist mayor of Los Angeles. He and his legal partner, Clarence Darrow, are most well-known for defending the McNamara brothers after they were charged with the bombing of the Times building in 1910.

After losing the race for mayor, he purchased 10,000 acres of land in the Mojave Desert near the San Gabriel Mountains from the Mescal Water and Land Company and set out populating his perfectly self-sustainable socialist city.

Civic Center (image from Frances Anderton’s blog)

Flyers read:

“Needs 900 single men and women and married men and their families.”

“This is the opportunity of a lifetime to solve the problem of unemployment and to provide for the future of yourself and your children.”

“We have land and water, machinery and experts for every department of production.”

“No experience as an agriculturalist needed. Men and women of nearly all useful occupations in demand. Every member a shareholder in the enterprise.”

Llano del Rio not only promised a fulfilling lifestyle, but also gender equality via architecture; Alice Constance Austin designed spaces that physically enforced and encouraged an equal playing field. Remember the year is 1915; the 19th amendment was ratified in 1920. Austin was acting on vision equally as radical as her socialist counterpart’s.

The first thing to go was the kitchen — in Austin’s mind, the agent of imprisonment. Each house was built without one; the city was organized circularly with centralized kitchens, daycares, and washing spaces. Austin even designed furniture in such a way to require less dusting via special jointing. All this was to considerably relieve the women of the colony of housework so as to have more time to actively participate in the politics of Llano del Rio.

The commune lost its water rights in 1916, and the onset of WWI lead to a mass exodus of many of its men. Llano del Rio eventually went bankrupt and finally disbanded completely in 1918.

While Llan0 del Rio sounds like an ideal existence to some, it is imperative to mention that the commune accepted only white members. This attempt at utopia was a fundamentally racist one.

The fight for kitchenless homes is reminiscent of what we call today white feminism. That is to say, the fight for liberation of middle class white women only while still using the blanket terms “women” and “feminism.” Austin’s vision did not consider women of other classes or women of other colors. So while her work was still undoubtedly done in the hopes of furthering the improvement of the status and lifestyle of women, it sacrificed and excluded the majority of them in order to realize physical actualization.

Despite its discriminatory policies, Llano del Rio remains interesting as a radical concept and as a story. Communes like this one are key components of California’s history; hit up “Hippie Modernism; The Struggle for Utopia” to learn more.